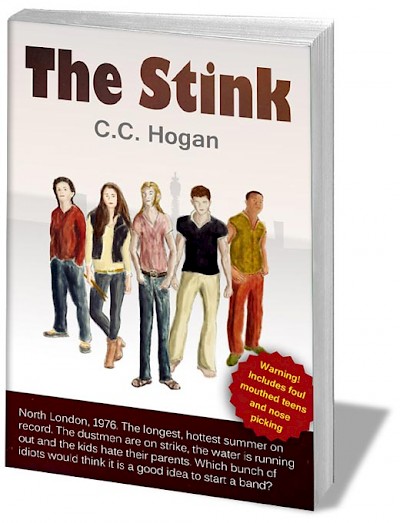

My next book to be published is The Stink. It is set in North London during the long hot summer of 1976 and tells the story of a group of sixteen year olds who have finished school and are trying to start a band.

I am not going to go into the full plot here, except to say that it is more or less a comedy with some serious issues thrown in and also involves a pretty horrific murder plot from the late nineteen fifties.

The reason this is set in the seventies is because when I was 16 years old is WAS the seventies. Also, I have a nagging temptation to give some historians a good kicking about that period. It can get very annoying to constantly be told that the seventies was when the country fell apart, when anarchy ruled in the streets, when we were all poor and scared, and our lives had hit rock bottom. Well what a load of crap, to be honest.

For instance, most teenagers didn’t like punk, which was why there were 10 times as many discos as there were punk venues (and why Disco is still here today, and the pure form of punk had died within 2 years). Most people who did like punk, didn’t dress like punks. Live music wasn't dead; I managed to go and see a couple of different rock bands every week without thinking about it, and none of them were punk bands. Yes, there were riots, and the dustmen always seemed on strike, but the vast majority of the population only saw “civil unrest” on their televisions, not outside their door, and got on with their lives quite happily with the rubbish picked up as normal.

There were some things that were pretty awful. Racism was one. This was the time the National Front got going properly in this country. I remember working a temporary job for a company in Brick Lane in London towards the end of the seventies and being asked by the people there if I wanted to go Paki-Bashing that night. I didn’t return there the next day. But mostly I saw racism confined to middle aged and older people who were still wedded to the nastiness you got in some working man’s clubs. My generation (apart from the skin-heads) hated that stuff. We would be the kids that got into New Wave comedy in the eighties, and we didn’t care where our friends came from as long as they were cool and not racist, of course.

But all in all, the seventies were sunny, they were crazy, and they were ours

Note about voice

To get full appreciation of this carefully crafted diatribe, please read this in a “Norff Lonnon” Accent. This will require you to be lazy about your TH sounds, not to bovver with consonants in the middle of words if they slow things down and to sound constantly surprised or mildly fed up about everything; your choice. And if your name is Smith, it is spelt with two effs, not one. Oh, and answer a question with a question. Example:

Parent: “Why did you trash the car?”

Car Trasher: “Why do I get blamed for everything?”

The Stink by CC Hogan

Chapter One - Introducing Smell

Copyright 2014 - all rights reserved

If you don’t wake up in the morning with your finger stuffed up your nose wondering where it had spent the rest of the night, well, you ain’t Smell. To Smell, small things like where his finger had spent the night could spoil his day as easily as someone dropping a piano on his brother’s Ford Escort. Actually, strike that. Smell would pay at least a fiver to watch his brother’s precious rust bucket flattened by a major chord, and let’s face it, he hadn’t seen a fiver since the last time he had poked around in his mother’s purse and his head was still hurting from that trip.

Waking up in the morning was an effort on most days for Smell and it seemed the more important the day, the more fun that was going to be had, the harder it was getting up. It was like some dreadful self-fulfilling prophecy where the greater the chance was that he was going to have something good happen to him, the less likely he was going to be awake for it. Smell worried that on the day he found out he had actually successfully chatted up a beautiful bird, he would never be able to wake up again.

“Melvin, I need your washing and you need to be up!” Smell cringed as the voice of his mum echoed through the floorboards. The sound, despite being muffled by the walls as if she had shoved a sock in her mouth, hit his ears at a volume that would give a low flying jumbo jet a run for its money. On cue, a Jumbo passed overhead at an almost apologetic volume. Melvin Arnold Lane. Smell wondered if being given an unspeakable name would count as mitigating circumstances as he thrust one, slightly grey foot from under the blankets and, with a gentle pop, removed his finger from his nose; that was one habit he was going to HAVE to get rid of before he got himself a girlfriend!

“What washing?” Smell tried to focus on the remaining patches of floor in his ten foot by twelve bedroom as he swayed into a standing position.

“That would be anything at carpet level that doesn’t look like the carpet,” his mother explained as she burst in through his door like Jack Regan. Jane Lane, who wished she had married a man with a different surname, was nearly a foot shorter and two feet wider than her son. Despite this, Smell was pretty sure she could pick him up and chuck him into next century, assuming the world wasn’t going to end in 1984, of course. “Oh, and in case you are thinking that there is probably something left in your cupboard that you can wear; there isn’t. Unless you count the pyjamas with teddy bears on that you got for your tenth birthday (top of your wish list as I remember.)”

“But what am I going to wear?”

“I suggest you steal one of your brother’s t-shirts again and you can wear the jeans you have been wearing for the last week; they appear to be more vertical than you are.” Smell was suddenly aware that he was lying down again, though he could not remember when that had happened.

“I will get your dad to cut your jeans off you later with his blow torch.” And with that, Smell’s mother jumped out of the window and abseiled down the outside of the house clutching most of his wardrobe. Or, at least in his half-awake imagination she did. He suspected that she had probably used the door as normal. Smell, cautiously glanced at the expanse of bright, lime green carpet that had been uncovered and wondered if they realized why he spent so much time covering it up with clothes.

It took Smell three attempts to get into his jeans; his mother had been right, they were definitely stiffer than they had been last week. He never had trouble getting the first leg in; it was trying to pick up the second high enough that caused him the problems. Eventually he managed to wedge himself between the cupboard and the wall and only gave himself the smallest of smacks in the face with his knee. Out on the landing there was an extended moment of hesitation where he debated between the bathroom, the bog and his brother’s bedroom. His biology eventually stepped in and decided for him, leaving his brother’s bedroom and the bathroom at two and three on his to-do list. Smell’s brother had been out since early morning. He had finished his A-Levels and had got himself a job as a milky while he worked out what to do next.

Richard “Dick-head” Lane was an organized sort of bloke as long as everything revolved around his precious car. He had passed his test back in January, but he had owned the car for over a year, spending everything he had on taking it from complete rust bucket to sublimely sleek and polished rust bucket with go-faster black and chrome around the rusty red body. To be fair, it was an Escort Mexico, so was pretty quick, or would have been if it were not so knackered. Either way, he was out on his rounds and would not be back till nearly mid-day, so Smell had the luxury of choosing just the right shirt.

“Hurry up, Melvin! Its lunch time and your bother will be back in a minute!”

“Oh…” Smell grabbed the nearest shirt from the neat pile near the bedroom door and legged it into the bathroom. Despite his nickname and his crispy denims, Smell was amazingly fussy about getting his teeth cleaned properly. He would spend ages getting the brush down every corner, around the gums and would even give his tongue a good scrub. Of course, this was not some goody-goody lapse, this was pure opportunism. If some girl ever consented to tonsil tennis, Smell wanted to be damn sure she came back for a rematch. He was yet to realize how important things like field-fresh armpits and clean jeans were to this scenario, but for your average 16 year old into rock ‘n’ roll, teeth were a pretty good start.

“Just coming up to mid-day and the temperature is pushing eighty degrees in the shade! It is one hot day folks… Again. In the news, there is continuing international condemnation over the deaths of Black students in South Africa protesting against the forced teaching of Afrikaans in their schools. Hose pipe bans are still in force across southern England and the government is talking about creating a Minister for Drought if the situation worsens. Meanwhile Thin Lizzy is banging it out with The Boys are Back in Town – THIS is CAPITAL RADIO ONE! NINE! FOUR!”

“And that is my tune!” Smell still had the toothbrush in his mouth and he spattered a curve of blue toothpaste coloured spit right across the mirror. He stood back and checked it out. It looked like one of those shooting stars from a Disney Film. Cool! Not wanting to spoil great art, he left it where it was as it started to trickle down the mirror and he leapt down stairs pulling on the suspiciously pink t-shirt as he went. Phil Lynott’s voice and bass hit out round the house setting the pace as his mother threw Smell’s noxious laundry into the Bendix, punctuating her well-aimed shots with each “BOYS are back in town” that Capital Radio blasted out through the transistor that sat on the kitchen cupboard. Smell was reasonably sure that the gas mask and elbow high contamination gloves that his mother was wearing was his imagination working overtime again, but he didn’t stop to find out. His brother would be home any minute and Smell needed to get out of the house before the T-Shirt was removed from his back, probably with a rake.

However, 16 year old stomachs have their own itinerary, and Smell’s pulled the breaks on his legs before he got to the back door. Damn, fuel needed! Rewinding the tape back to the larder, Smell reached inside and grabbed a couple of slices of Nimble bread (tasted like cotton wool flavoured with extract of nothing) and a small square tin of corned beef. Okay, so not exactly pre-prepared, but Smell had tried the combination before and at least he hadn’t died. He snatched a banana for extra flavoring and stepped out into the Sun.

“Don’t you go dumping that tin outside! Get it into a bin.” His mother missed nothing, and neatly caught the flying and empty tin as it was tossed through the window. Quite how Smell has consumed an entire tin of corned beef within two steps of the back door she really didn’t want to know; just as long as he hadn’t got any on the T-Shirt. Back in the sun and Smell, now completely immersed in the idea of putting everything in his life to music, leapt over the front gate, caught his foot on a bit of the neatly trimmed privet hedge and disappeared into the front garden next door. Lying on his back, the mid-day sun drying out the smear of corned beef on the T-Shirt, he slowly became aware of being stared at upside down by a small, tubby, white dog, mouth full of two slices of Nimble Bread.

“Well, I don’t care what the ad says, mate, you ain’t never gonna ‘Fly like a Bird.’”

“Woof,” agreed the dog who had sudden, irresponsible but joyous visions of scaring the hell out of all the pigeons that dive bombed him in the back garden.”

“You are welcome to it, mate.” And with that, Smell leapt to his feet, bowed majestically to Mrs. Finch, the owner or the small white furball, who was standing in her front window frowning, and let himself out of her front gate politely. One more bow and he ran for it towards the old embankment.

Sixteen years Smell had been on this planet and he was pretty damned sure, mostly because the papers kept telling him, that this was the hottest summer anyone decent could remember. In many ways it was pretty cool; having just done his O-Levels, Smell had been kicked out of school three weeks before normal so he and his friends had a long summer to look forward to. Great weather would make it pretty damned serious, as far as he was concerned. On the other hand, it was playing seven types of hell with his feet and he was fairly sure he was going to have to dump the sneakers before they rotted. Anyway, time for a bit of a new image. Glam had gone boring, the zips and black leather the Ramones were touting looked worryingly nasty, not to mention way too hot, and there was no way he was going to wear the Spandex of the disco scene! So, jeans, shirts and sandals were going to be his new mantra. He knew he risked being slated as a stinking hippy, but in this weather, he had stopped caring. And anyway, Aroma seemed to like the more folksy and gypsy stuff, being Irish as she was, and what Aroma said was Gospel, as far as Smell was concerned. Ah, yeah, Smell had promised himself to not think about Aroma too much. That line of dementia was causing him trouble. A drummer is a drummer is a drummer; you weren’t meant to start fancying them even if they were a beautiful and gorgeous Irish girl with big green eyes.

Smell lived on a pretty typical sort of street in North London. It wasn’t a wealthy place and neither was it a council estate, it was a kind of in between, nothing much to say for itself place that you find all over the South East of England. The houses were mostly semis with a very occasional detached house put in between. All the front rooms had small bays and there were fake wooden beams up in the eaves of the roof. Beneath the downstairs windows was brick, but the rest of the house was white painted pebble dash. The window frames were wood, the gutters cast iron and these houses would probably stay sat where they were put for centuries. They were popular with a certain age of man because they were a “solid build,” and they were popular with housewives because the gardens were a good size and had plenty of room for hanging washing out. All in all it was a safe, dependable and completely predictable sort of street and Smell hated it. Well, hate was probably a strong word, but then Smell always hated things first and then sort of modified his views as he went along until he got to the point where he forgot that he had hated anything in the first place. And if you were mad enough to say, “But you said you hated that,” then you would probably just get yourself hated, at least until Smell forgot he had hated you. Actually, none of Smell’s friends found this arrangement at all odd since they adopted more of less the same policy most of the time anyway.

The road, Birch Tree Avenue, was a long, not too steep hill that was bordered by Cherry trees. Don’t ask. About half way down it was crossed by Grub Street which predated about everything else round here, hence the odd name. Where it crossed, the designers of the estate had put a good sized roundabout to accommodate a wonderful ring of huge and ancient Elm trees; that was until five years before when the whole lot had died. Now it was just a grass mound with a sad, four foot tall oak sapling in the middle. Smell missed those huge Elm trees; they had a warm feeling about them and were like gate keepers against the invading cherry trees. When they had been cut down, he asked one of the council workers if they would be planting Birch trees instead. The workman looked at Smell with a puzzled face. “Why?”

Smell thumped into the red pillar box that was on the roundabout, shook the dizziness out of his head and turned right into Grub Street. He had no idea why Grub Street was called Grub Street; maybe it was because it had a lot of grubs in it at one point, or maybe it was not very clean, though that would be grubby street. Or … whatever. Smell wanted to be still living in the seventies when he got to the end of the road, so he stopped wasting time working out the name. Grub Street, being older than the other roads that made up the estate, wound down the hill rather than ran straight. It still had the same houses as the rest of the estate, but occasionally there was something different from an earlier age. These were probably old farmhouses, Smell thought, since they were bigger and often set a bit farther back than the rest. There was one near the bottom that he really liked. It had a sort of gothic look to it, was pretty big and had a tall wall round it and the local kids called it the Ghost House. If he hadn’t known who lived there his imagination would have probably taken over and come up with some pretty amazing, but unlikely solution. As it was, this was the home of the Doherty’s; a large family of successful but fun loving Irish from Dublin. The youngest of them was Alannah, otherwise known as Aroma, the drummer of The Stinks, and Smell fancied her like crazy. But all of that was for later. Smell had an appointment with Haze down at the railway sheds and he better get a move on; he had said he would be there an hour ago.

Past the Ghost House, Grub Street turned to the left and headed alongside an old railway embankment. Although this was suburban London, and was pretty well built up, this bit could have almost been in the country if you squinted a bit and ignored the tatty row of lock ups on the other side. Smell jumped over the old linked wire fence and scrambled up the embankment. The railway line had long since been taken away, even before Beecham got his hands on the railway system, and no one round here even remembered the line, let along any trains running along it. It was mostly overgrown, but the top of the embankment where the line had been was surprisingly clear. Smell supposed that is was probably the stone foundations for the track, or maybe too much tar and coal over the years or something, but he didn’t really know or care much about it; it was just part of his route and that was all he needed to know. Very few people came this way; it was just off the radar. As far as most people knew it didn’t really go anywhere at all, so why bother with it? Smell knew different, of course, but he was damned sure he wasn’t going to let on to anyone else.

Where he had climbed up onto the tracks, or where the tracks had once been, he could look up and down for quite a way. It was pretty straight here, but the trees that had grown up either side meant that you could not see anything below the embankment. Behind him the track ran about two hundred yards before it hit a high fence. Behind that lay a big scientific institute and the line ran no farther. Ahead of Smell, the line ran for some considerable distance before slowly bending off to the right. Smell headed off this way. He liked it up here. Although he could hear London beyond the trees and bushes, he could not see it at all. The sound was mostly a dull rumble that never really went away. Some of that came from the A1 which was not far, just a few streets beyond the houses and was six lanes of traffic heading in and out of the City, but a lot of it was just London itself; the people tramping around, the buildings breathing in and out, small roads, large roads, parks, shops, offices, homes, all messed up together into one huge snoring dragon. Sometimes you would hear little pieces of detail emerging from the roar. A small dog would bark at a shadow, or a child who was a couple of gardens away would scream as she fell over her own feet, or maybe a police car with its two-tone wah-wah-wah-wah changing pitch as it went from one side to the other.

And further into the sound, deeper, almost hidden, was a longer, softer roar. That was the centre of London and was the backdrop to everything anyone living in this huge metropolis ever did, thought, saw or felt. Smell has visited other cities. He had cousins that lived in Manchester and that place was no little town. But it did not have that London undercurrent; that solidity that said that this place had grown far beyond the plans of its makers and had now taken on a life of its own, a symbiotic relationship that fed off and fed the inhabitants throughout the Greater city. More than seven million people lived here, and it would only get bigger, not smaller. Smell’s father had once mentioned the London Ringways Plan. This was one of those mad schemes dreamed up by the GLC that had got chopped and changed all over the place. But eventually, some of it had been built with a section North of where they lived called the A1178. It was getting renamed however to the M25 and there was talk of it eventually encircling London completely. Yeah, and pigs might fly! Many people said that if it happened, there would be nothing stopping the gap between Greater London and the ring road being stuffed with houses.

“And then the dragon will be bigger,” Smell said out loud to no one.

Smell walked over an ancient railway bridge crossing Tangle Lane and walked round the bend in the tracks. He supposed that Tangle Lane was a small country lane at one point, pushing its way beneath the line like a mole making a tunnel. But now it was a dirty, smelly, potholed road that lead to small workshops and light industry. You could get everything from MOTs to your saucepans re-enamelled down there. Many of the businesses were owned by Asian and West Indian families and they were a tight knit group. Smell went down there with his father every time their old Cortina started making funny noises. Frank’s was the place they went to. Frank was an old guy with white stubble peppering his African skin. Smell loved the bloke. There was nothing he did not know about cars and he could keep anything running forever; a good thing since the old Ford they owned had seen its best many years ago. Haze’s uncle also had his builder’s yard down here and was fiercely protective of his immigrant neighbours. It wasn’t always easy being black in London, he had told Smell. Although they did not have much trouble with racism in this area, there were some skin-head gangs and they tended to target the small industrial estate. The West Indians didn’t like calling the police; if the coppers sent in the SPG, they could be worse than the Skins. So Haze’s uncle used to call the local station on a direct number, put on his poshest, whitest accent saying, “I am terribly sorry, but we appear to be having a little bit of trouble. Could you send a couple of sergeants down here? And tell the Super that I will see him at the Lodge on Sunday.” Worked every time.

Sending older sergeants was a clever move. They knew everyone round here, including the parents of the skins. They could resolve things in a way that a truncheon would just make worse. But if it did get out of control, they could wave a baton so well that would make even the SPG wince. At sixteen, Smell had already been working on the healthy anti-establishment ideology that you do at that age, but even he had to admit to a serious respect for these men.

Beyond the bridge, the railway line curved first to the right and then to the left and then started widening out. This was just a single track line and seemed only to lead to a small group of engine sheds that now confronted Smell. They were not huge and Smell and his friends suspected that this might have been a private line owned by a factory or something in Victorian Times. Certainly this had all been abandoned for so long that none of them had found anyone who knew what they were talking about, let alone remembered what it had been used for. Haze had commented that this was a bit beyond weird – it was bleedin’ mystifying. I mean, here were four large sheds, one of them long enough to take several locos in a row, complete with maintenance pit, a big enough area for eight or ten shunting lines and no one knew about it? What was more, it was all in pretty good nick, all told. Yeah, there were a few broken windows, and even a few skeletons of the birds that had broken them, but most of the windows were more or less intact and within the sheds themselves there were few weeds or anything.

As Smell walked up to the platform that ran down the side of the main shed, he heard a yell from inside.

“I have been waiting here for sodding ages, yer bastard!” Haze had a way of summing up situations that was as concise as it was occasionally unprintable. His father was from Liverpool, and the faint Scouse accent that Haze had inherited made swearing so much better than Smell could ever do that Smell had almost given up swearing out of pure respect. The unmistakable figure of Haze emerged from the building onto the platform and sat down on the edge, his legs hanging down like a couple of wooden posts. He had an easiness about him that sometimes scared Smell. Haze was one of those people who were born muscular; not the sort of muscles that stood out like a body builder, just thick arms and legs and, well, the rest of him really, that was muscle rather than fat. Running into him was like throwing yourself against a rubber clad concrete wall; it doesn’t hurt, but it doesn’t move either. He was also tall; a good foot taller than Smell. Smell reached a hand up as he walked to the platform and Haze hoisted him up and swung him onto the platform next to him.

“I am not that late, your watch must be wrong.” Smell picked a loose stone out of his old sneakers. The downside of this place is that the ground was mostly gravel and shingle. They had tried playing footy here, but got fed up of looking like they had been flayed.

“You have been that late for as long as I have known you and even if I didn’t wear a dead accurate Timex watch I would assume that you are late and would be right too.” The downside of Haze was that he was also very sharp and could get to the end of a long, complicated sentence with such neatness as to leave their English teacher stuttering. Smell swore.

“Maybe. I had a washing issue.”

“Yeah, my mother had a clear out today too – must be a conspiracy.”

“So what we doing down here? I thought we were trying to work out some rehearsal space for the band?” Smell, Haze and a few others had started putting a band together. They had this mad dream that they would spend this long summer following their O-Levels being really cool and rocking their world. To be fair, they could actually play, at least individually, and had even got a couple of songs sorted out. Putting that together in a way that didn’t sound like two old blind dogs fighting over a dead cat was proving a bit harder, and they had now been banned from every garage belonging to every parent they knew, which was why they needed rehearsal space.

“Well, down here is what we got.” Haze was being bleedin’ obvious again and Smell growled under his breath.

“In case you hadn’t noticed, we ain’t some finger-in-yer-ear folk band! We are pure rock ‘n’ roll, mate, complete with Strats, Rickenbacker bass, an electric piano and microphones. If we don’t have power we are just going to sound like some idiots off Play School or Jakanory.”

“Indeed, young friend…”

“I am only a month younger than you.”

“Young ISH friend. Anyway, my uncle has the solution. He’s got an old generator he said we can have as long as we come and drag it away. It means keeping it filled up with four star, but as long as we don’t start plugging in too much to it, we should be okay.”

Smell had visions of them all stinking of leaded petrol as they walked in convoy along the track carrying 1 gallon cans. And at 77p a gallon at the local Esso, they were also going to have to save up.

“Yeah,” agreed Haze, “but we won’t have to fork out on rehearsal rooms. Smell nodded. It actually made sense, which was a bit of a first for one of their plans.

“How much does this genny weigh?”

“No idea,” said Haze as he jumped down off the platform. “But we are going to need help, I reckon. Coming?”

“Whatever.”